“Film is truth 24 times a second, and every cut is a lie” -Jean-Luc Godard

The French New Wave or La Nouvelle Vague constitutes a vital movement in film history. Originating in the late 1950s, much of modern filmmaking is still firmly rooted in the elements of filmmaking implemented by the French New Wave films- from the works of Quentin Tarantino to Martin Scorsese to A G Inarittu.

But what do we really mean by the French New Wave? How did it begin? How was it any different from numerous other Film Movements that have arose over the years?

With the end of WWII came the end of Nazi censorship in France. Foreign Films (and banned French films, such as those of Jean Renoir) were allowed back into French cinemas for the public to view. American filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, and John Ford- who were seen as artists who used the camera as their paintbrush- began influencing French filmmakers. This was the first time the authority of the filmmaking process shifted from the production house to the filmmakers.

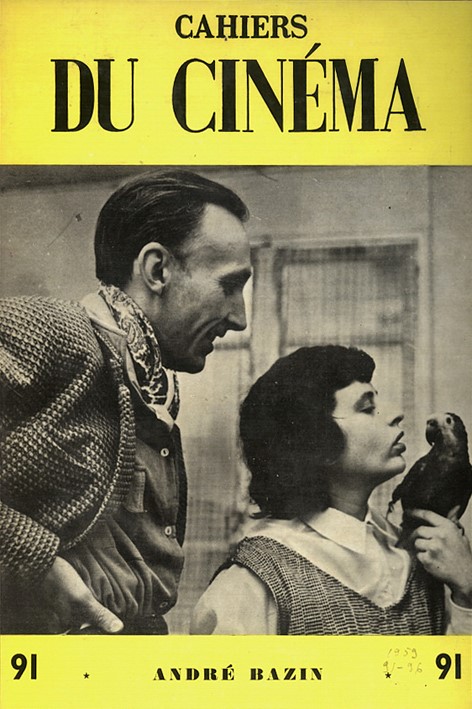

The French New Wave began in 1951 with a group of film critics and cinephiles who wrote for Cahiers du Cinema, a famous French film magazine owned by Andre Bazin. These critics- including Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, and Eric Rohmer- pushed against big film studios controlling the creative process and demanded full control over their films.

After their ideas started gaining recognition among a larger circle of young intellectuals, the group of critics decided to begin directing feature films of their own. Since their methods rejected big studios, these directors had to work with very small budgets in order to make their films, which led to several quintessential aesthetics of the movement.

For decades, mainstream filmmaking, especially from Hollywood, set the standards and norms on how to make a film. The French filmmakers learned these rules- and then hurled them out of the window. French New Wave films employed smaller cameras extensively. These lightweight cameras were often ‘freed’ from the tripod and handheld, invigorating the films with a renewed creative outburst. Non-linear and fragmented editing was yet another major contribution. For decades, each shot quite predictably led to the next shot, leaving no gaps in the underlying logic to keep the audience from being confused. While old Hollywood films were all about immersive, entertaining narratives, French New Wave films wanted to challenge audiences and keep them from getting complacent while watching. These films dealt with intellectually involving topics like Existentialism and the Absurdity of Existence. The films often featured long takes that allowed audiences’ minds to wander and bring their own experiences into the cinema.

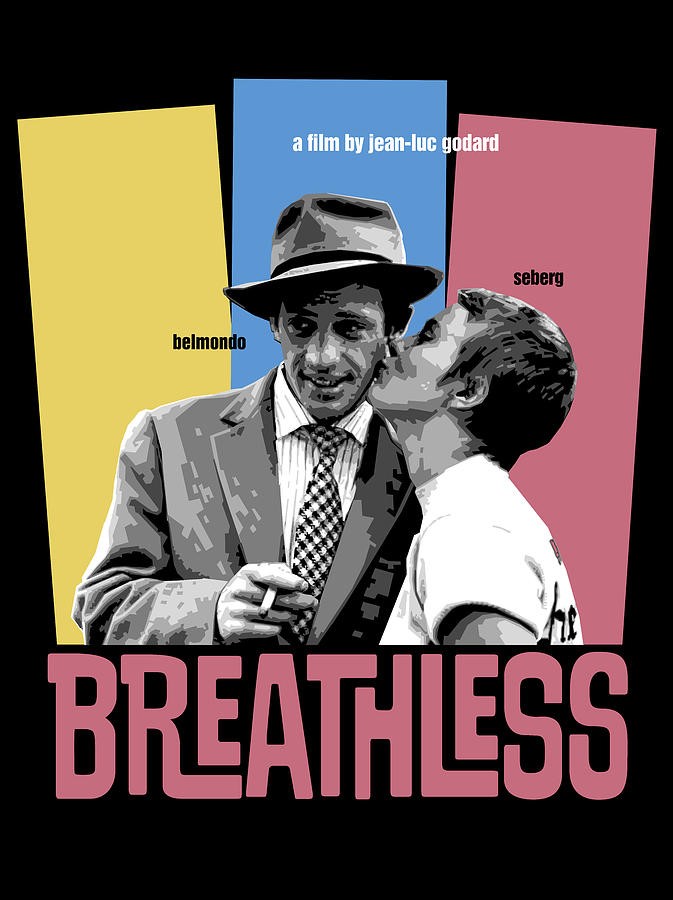

Arguably, French New Wave’s most notable international figure is Jean-Luc Godard. Widely acclaimed for his inventiveness with numerous aspects of filmmaking including camera movements, dialogues and storylines, his full-length feature debut came with 1960’s Breathless; a pop-culture inspired narrative filmed in a revolutionary style. The feature film emphasizes the presentation of the story, more than the story itself, much like Bazin’s notes on audience perception of a film.

However, the New Wave filmmaker whose films garnered perhaps the greatest attention among mainstream Hollywood directors of the time, was Francois Truffaut. He was greatly influenced by Hollywood film, specifically the work of Alfred Hitchcock, whom he revered. Truffaut’s full length feature debut **The 400 Blows**, released in 1959, and one of the most stirring films ever made, tells the story of a neglected Parisian boy who gets acquainted with the hardships of life at a very young age. This deeply autobiographical film set the tone for Truffaut’s latter works and established him as a deeply humanistic and elegiac director.

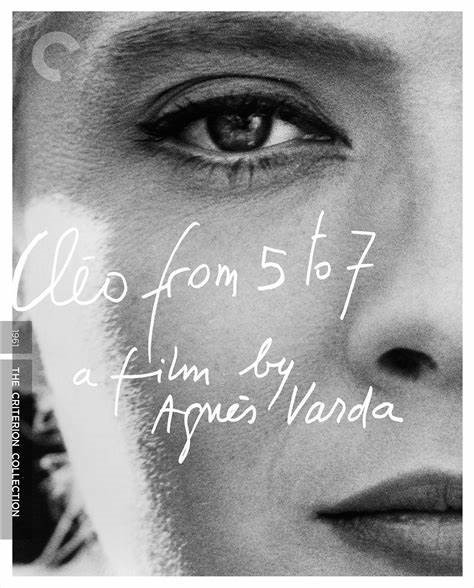

While the Cahiers(Right Bank) were off making groundbreaking pieces of cinema, the Left Bank was on the other side of the New Wave Movement. The filmmakers of the Left Bank were much more concerned in challenging film form and creating very experimental films. One of the primary filmmakers of the Left Bank, Agnes Varda, was a photographer before making her debut La Pointe Courte in 1955- which would become one of the greatest Left Bank films. Varda would later go on to make the more acclaimed Cleo from 5 to 7 which included a cameo from Jean-Luc Godard. Another pivotal figure of the Left Bank was Chris Marker who gained a massive critical acclaim owing to his short film La Jetee (1962). The film was a science fiction narrative about a post-nuclear-war experiment done in time travel, filmed almost entirely in a montage of still images.

French New Wave has had a profound impact on modern cinema and media in general. American filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese have made films aesthetically similar to the movement. Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction and Scorsese’s Taxi Driver are arguably the directors’ Magnum Opi, as well as their odes to the French New Wave. Pulp Fiction employed the handheld aesthetic, and used jump-cuts throughout the film to complement its fragmented narrative. Taxi Driver presented a small production and had the feel of a documentary being shot in real locations. American Sci-Fi films like Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys (1995)- inspired in many ways by La Jetee- and Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) which was in many ways a homage to ‘The 400 Blows’, testify the legacy of the movement.

As the years pass, the reels roll ‘round and round in the widening gyre’; we the spectators, were bestowed the glimpse of an immersive phantasmagoria by the French New Wave movement, as we scrolled past another brilliant page of the romantic elegy, that is, Cinema.